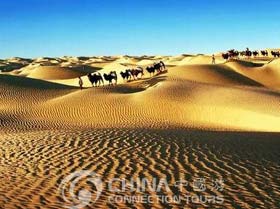

Dunhuang, meaning brilliant or magnificent, was once an important city. Its position at the intersection of two trade routes was a favorable one and Dunhuang flourished. In the first century B.C., when Emperor Han Wudi began expanding the empire westwards, it served as an important way station on the main trade route between China and Central Asia. The coming and going horse and camel caravans carried new products, ideas, and arts and sciences east and west.

Dunhuang, meaning brilliant or magnificent, was once an important city. Its position at the intersection of two trade routes was a favorable one and Dunhuang flourished. In the first century B.C., when Emperor Han Wudi began expanding the empire westwards, it served as an important way station on the main trade route between China and Central Asia. The coming and going horse and camel caravans carried new products, ideas, and arts and sciences east and west.

Today Dunhuang is best known for the nearby Mogao Caves that contain Buddhist frescoes, ritual objects, and documents dating from the 4th to the 12th century AD. The frescoes are considered to be the best-preserved examples of their kind in China.

Dunhuang and the Silk Road

The oasis town of Dunhuang, known for its melons and grapes, became a major staging post for traders and for missionary monks and pilgrims. It was one of four garrisons that assured Chinese control over the trade routes to the western regions. The trade route from China to the West that grew and prospered during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) and flourished to the end of the Yuan Dynasty (1279 AD) became known as the Silk Road. An ancient traveler leaving China on this road passed through Dunhuang before braving the many hazards of the journey westwards through East Turkestan (present-day Xinjiang Province). Dunhuang was located close to the parting of the northern and southern routes that skirted the impassable Taklamakan desert.

Silk, porcelain and other prized goods were carried along this seven thousand kilometer braid of caravan trails from China across Asia to the eastern Roman Empire on the shores of the Mediterranean, and south Asia. Persian and Sogdian merchants traveled the length of the route, and were familiar sights in the Chinese capitals of Chang'an (present-day Xi'an) and Luoyang. This route was used by Buddhist monks from China and Korea traveling west in search of images and scriptures, and by ambassadors and princes from the west making the long journey to China.

Silk, porcelain and other prized goods were carried along this seven thousand kilometer braid of caravan trails from China across Asia to the eastern Roman Empire on the shores of the Mediterranean, and south Asia. Persian and Sogdian merchants traveled the length of the route, and were familiar sights in the Chinese capitals of Chang'an (present-day Xi'an) and Luoyang. This route was used by Buddhist monks from China and Korea traveling west in search of images and scriptures, and by ambassadors and princes from the west making the long journey to China.

Vessels made of gold and silver and the techniques for working these metals, fine glass, fragrances and spices, exotic animals such as lions and ostriches, new fruits such as grapes, dancers, musicians and their instruments, all came to China along the Silk Road. Some arrived as diplomatic gifts and others as objects for trade, mainly in exchange for silk. After the Tang dynasty, trade between China and Europe was mostly by sea, and trade along the Silk Road was greatly reduced. Dunhuang was left in isolation.

Geographical Features

Located at the west end of the Hexi corridor, Dunhuang is a tiny oasis fed by the Tang river, surrounded by the Qilian, Beishan, and Dieshan-Minshan mountains, and the Gobi desert The Yellow River and its tributaries, the Dang and Shule Rivers, irrigate the city. The climate is dry. The annual average temperature is 9.3 C (48.74 F), but ranges from 24.7 C (76.46 F) in July to -9.3 C (15.26 F) in January. The temperature varies greatly from day to night. Summers are hot with the highest temperature over 40C (104 F). The annual average rainfall is 39.9 mm, nearly all of which falls in spring and autumn.

People

The total population of Dunhang City is 100,000. Hui, Tibetan, Manchu, Dongxiang,  Yugu, Baoan, Mongolian, Kazak, Tu, Sala, Manchu and Han nationality people live here peacefully together.

Yugu, Baoan, Mongolian, Kazak, Tu, Sala, Manchu and Han nationality people live here peacefully together.

History

For centuries, Dunhuang marked the western limit of direct Chinese administrative control and military authority. Located near one of the important routes across Eurasia, the city was subject to a variety of cultural influences. Much of Dunhuang's history has been well documented, while, unfortunately, that of many similar cities in Inner-Asia has been lost.