In China the potter's workmanship was lifted above the utilitarian level and became a fine art. The great work of the imperial potters at the peak of their excellence has never been equaled in modern times. Chinese Pottery was made long before history was set down in writing. A coarse gray earthenware was made before the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 BC), and a finer white pottery was also made during this era. These vessels resemble in size and shape the Chinese bronze vessels of the same period, and it is likely that the bronzes were first copied from pottery.

In China the potter's workmanship was lifted above the utilitarian level and became a fine art. The great work of the imperial potters at the peak of their excellence has never been equaled in modern times. Chinese Pottery was made long before history was set down in writing. A coarse gray earthenware was made before the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 BC), and a finer white pottery was also made during this era. These vessels resemble in size and shape the Chinese bronze vessels of the same period, and it is likely that the bronzes were first copied from pottery.

It is from the Han Dynasty (202 BC- 220 AD) that the history of pottery making in China is ordinarily traced. The ancient Chinese buried their dead with pottery bearing images of people, animals, and possessions dear to them during life.

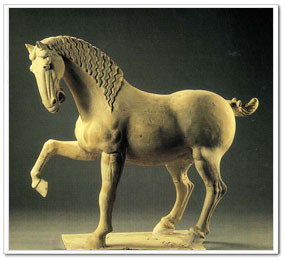

The period of disunity (220-581) is noted for vigorous modeling of figures, particularly of animals. The pottery horses of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) are among the most celebrated examples of ancient Chinese art Glaze was probably first used on earthenware in the Han Dynasty. By the time of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), pottery of simple design was decorated with monochromatic glazes. Celadon, or sea green, is probably the best known of these glazes.

Although crazed, or crackled, glazes appear to have been used before the Song Dynasty, they are commonly associated with this period. This shrinking and cracking of the glaze, due to too rapid cooling, was probably first an accident of firing. The resulting effects were so attractive that crackled glazes became a studied effect in finer wares.

Chinese Porcelain gradually evolved in China, probably during the Tang Dynasty. It grew out of earthenware by a process of refining materials and manufacturing techniques. This true porcelain, sometimes called hard-paste porcelain, was a combination of kaolin, or China clay, and a type of feldspar or China stone. These ingredients were called by the Chinese the body and the bone of porcelain.

The principal porcelain factory in China was the imperial plant at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province. The Jesuit missionary Pere d'Entrecolles described the city and the art of porcelain making in two letters written in China in 1712 and 1722. These brought to Europe for the first time a detailed account of Chinese porcelain manufacture. He described the great porcelain-making center of Jingdezhen as holding approximately a million people and some 3,000 kilns for ceramics.

The principal porcelain factory in China was the imperial plant at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province. The Jesuit missionary Pere d'Entrecolles described the city and the art of porcelain making in two letters written in China in 1712 and 1722. These brought to Europe for the first time a detailed account of Chinese porcelain manufacture. He described the great porcelain-making center of Jingdezhen as holding approximately a million people and some 3,000 kilns for ceramics.

The glazes and decorations made at the imperial factory were intended to reproduce natural colors. Some of the best-known glazes are celadon; peach bloom, like the skin of a ripening peach, apple green, oxblood, and a pale gray blue. The decoration called cracked ice is said to have been inspired by the reflection of a sunny blue sky in the ice of a stream cracking with the first spring thaw.

The rice-grain decoration was achieved by cutting out the decoration from the porcelain body before glazing. The glaze then filled the cutout portions, which remained transparent after firing. Rose or soft pink, green and black were the dominant colors.

The porcelains of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) were noted for boldness in form and decoration, with great variations in design. They include the blue and white ware, huge vessels for the imperial temples, and delicate white eggshell porcelain.

Some fine white porcelain was made at Dehua in the province of Fujian in South China from the 1400s to the 1700s. Some of this ware was brought to Europe by early traders, where it was known as Blanc de chine. It provided many models for the early European porcelain makers.

During a rebellion in 1853, the imperial factory was burned. The rebels sacked the town, killing some potters and scattering others. The factory was rebuilt in 1864 but never regained its former excellence. With the end of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the long history of Chinese porcelain making drew to a close.